After years of extreme abuse, a teen finds love- and a mission – with his new adoptive parents.

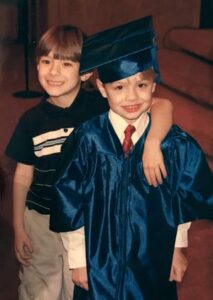

Six years ago, Taylor Hart DuRard watched his big brother die because of child abuse in the home. DuRard and his adoptive parents now work hard to give foster teens hope

![]() Brad Schmitt, Nashville Tennessean

Brad Schmitt, Nashville Tennessean

Carrie DuRard paced outside the courtroom for a few moments before latching onto her husband, Jase, who smiled big.

“Oh, I don’t know what I’m so nervous about,” she said in a hallway in the Williamson County courthouse in Franklin. “This is one of the happiest days of my life!”

The DuRards were minutes away from adopting their 18-year-old foster son, Taylor, who’d been living with them for two years in their big modern, safe and loving home in Franklin.

A dozen or so relatives, friends and case workers showed for the adoption, ready to applaud, eager to celebrate the teenager’s transformation.

For years, Taylor Hart lived through hell, surviving beatings, food deprivation and other forms of abuse and neglect at the hands of his biological father and stepmother, according to Taylor, police officers in Murfreesboro and state authorities.

His older brother, John, didn’t make it. He died on May 26, 2016, at 13 years old.

That happened after the boy’s stepmother found he’d vomited in his bed, pulled him from his top bunk to the floor, kicked the semi-conscious teen down the hall to the bathroom and forced him to stand in the shower, according to police, prosecutors and Taylor.

But John fell and hit his head, losing consciousness. He died later at Vanderbilt University children’s hospital, right after his younger brother touched his hand and made John a promise.

“They’re gonna pay for what they’ve done to you,” Taylor said. “I will not stop. They will pay for what they’ve done to you.”

The boys’ stepmother, Emily Hart, is serving a six-year sentence after pleading guilty earlier this year to attempted aggravated child abuse. Her husband, Chris, the brothers’ biological father, remains free.

The lawyer for Emily and Chris Hart, Murfreesboro attorney Bert McCarter, did not respond to two emails and a phone message from The Tennessean seeking comment for this story. McCarter’s assistant also did not respond to the emails.

The lawyer for Emily and Chris Hart, Murfreesboro attorney Bert McCarter, did not respond to two emails and a phone message from The Tennessean seeking comment for this story. McCarter’s assistant also did not respond to the emails.

Taylor Hart is now 18, and he’s now Taylor Hart DuRard, keeping Hart as part of his name to stay connected with his late brother.

He sat down with The Tennessean to talk about John, the abuse, his new parents and the nonprofit they’re starting in his brother’s name to help teens in Tennessee’s foster system.

“Right now, I’m living in a dream,” Taylor said. “This was the end goal I thought would never happen − a family that loves me no matter what, a family that I can trust.”

‘I just got hit in the face by an adult!’

But trust came hard to Taylor, who said he remembers abuse starting soon after his divorced dad got married again in 2009, this time to his high school sweetheart, Emily Hart.

Taylor, then 5, got some ice cream out of the freezer and started eating it without asking his dad or stepmom for permission.

When Emily Hart saw the boy eating ice cream between two pieces of bread, she got angry, told Taylor he was stupid and hit him hard across the face with an open hand. His stepmom ordered Taylor to go to his room and stand in the corner, he said.

Taylor was shocked.

“I was like, what happened? She hit me in the face! I just got hit in the face by an adult!”

The next day, a Sunday, the family came home from Third Baptist Church in Murfreesboro, and Taylor remained in trouble. His stepmom told him to go to his room, stay away from his toys and stand in the corner, he said. Taylor, again, remembers being surprised.

“I still have to stay in the corner? This isn’t normal. What am I supposed to do? I guess I’ll just stand here and look in the corner.”

The abuse escalated three years later, when Taylor was in third grade, he said. That’s when food restriction started, he said.

“It started this way − if we were good, we would get what everyone else gets. If you’re bad, you get peanut butter sandwich and tortilla chips,” he said. “Then it became, if you’re good, peanut butter sandwiches, bad, nothing.”

For many months, Taylor and John missed as many as five dinners a week, Taylor said. That’s when the boys started digging into trash cans, stealing food from other kids, raiding a teacher’s snack drawer, asking classmates for lunch leftovers.

“It started as shameful,” Taylor said, ” but it just became what we did. We’ve gotta find food; if I don’t, my stomach will hurt all night.”

Some classmates made fun of the Hart brothers. Some helped. Several teachers fed the brothers, and then, those teachers noticed the boys showed up with cuts and bruises.

In fourth or fifth grade, Taylor said he started being mean to other kids and getting in fights. One teacher asked what was going on at home, and Taylor said, “I don’t want to talk about it.”

“Well, then write it down,” the teacher said. “And write down what you’re eating.”

John also started writing notes to teachers.

The brothers told each other super hero stories at night

One from Taylor dated April 9, 2014 said, according to police:

“Remember when I told you that all that I told you was a lie[?} it really wasn’t because my dad said that if I told you that then he’d stop but he didn’t[.] he tricked us he said that he’d never stop until he died. He’d keep not feeding me and beating me.”

Teachers gave the notes to police and to the Department of Children’s Services, and state investigators started showing up at the house, sparking more anger from the boys’ parents. The father and stepmother kept hitting them in the face with open hands and kept restricting food, kept telling DCS there was no food restricting or abuse in the home, Taylor said.

The boys were banned from leaving the room to stop them from sneaking into the kitchen for food, Taylor said. Their father and step mother put motion detectors in their room − and even using the bathroom became restricted, Taylor said.

The boys were banned from leaving the room to stop them from sneaking into the kitchen for food, Taylor said. Their father and step mother put motion detectors in their room − and even using the bathroom became restricted, Taylor said.

The boys started using a bucket in their room and dumping it out a window. They sometimes urinated and defecated on the floor, Taylor said. They sometimes showed up for school in soiled jeans, and teachers often had a change of clothes for them, Taylor said.

“There were times when we’d go to bed and we’d both be physically in pain,” he said. “Sometimes we’d stay awake and tell super hero stories to each other to get our minds off pain.”

But nothing could distract John the night he was lifeflighted to Vanderbilt.

Taylor stayed in that house for two years after his brother died.

Two more years.

And the abuse continued.

One day, Emily Hart beat Taylor in the face until he was bleeding from his mouth and his nose after Taylor had grabbed extra snacks from Vacation Bible School, Taylor said.

“You’re doing the same things John did!” his stepmother screamed, according to Taylor.

“So you’re going to kill me too?” Taylor shouted.

The beating continued until he passed out, Taylor said. When he regained consciousness, his stepmother yelled at him to stop bleeding on the floor.

DCS finally interceded and got Taylor and his younger sister, to the house of some safe relatives, where his sister remains today.

From there, DCS placed Taylor with a couple the teenager met four times over Zoom.

They ain’t scared

Carrie and Jase DuRard, working at different health care companies, first met in 2007 through their mutual love of triatholon competitions. Jase already had two children, and when they got married five years later, they decided to not have more children.

But they kinda did.

Jase started mentoring young men who crossed his path who needed direction. One was the couple’s dog walker; another was a work colleague who ended up living with the DuRards for a while. Carrie DuRard wanted to do more.

Jase started mentoring young men who crossed his path who needed direction. One was the couple’s dog walker; another was a work colleague who ended up living with the DuRards for a while. Carrie DuRard wanted to do more.

“We had the space, the heart, the time, the desire,” she said. “We’d seen these young guys and our bio kids continue to flourish.”

So the DuRards became foster parents. Most placements were for just a few days or weeks.

Then their foster agency sent over information about Taylor Hart, who’d suffered so much abuse − but the DuRards weren’t intimidated. In fact, they were stunned that Taylor didn’t have more behavior issues.

“Taylor had all this trauma,” Jase DuRard said, “but he wasn’t stealing cars, or really acting act out all. We felt like we’re equipped to deal with this.

“We believe if you give a kid options and boundaries that are clear, if you show them you’re not going away no matter what they do, they will do the right thing.”

The first few months were tricky. Taylor brought in serious trust issues, and the DuRards consistently strived to be trustworthy.

There were some emotional breakdowns − Taylor started sobbing loudly one day and seemingly couldn’t stop.

“I’m holding him and repeating in his ear, ‘You’re safe, you’re here, you’re safe, you’re here,'” Jase DuRard said. “I repeated those dozens of times until he stopped shaking and stopped crying.”

Soon, Taylor started to have that trust.

“It’s good to know if there’s something I’ve done that’s not good, they still love me,” he said.

After two years, the DuRards asked Taylor to legally become part of their family. Though he loved them, Taylor asked himself some tough questions about that move. How do I stay connected to John? How do I stay connected to biological family members who are safe and loving?

The three of them worked through it together, and they gathered Nov. 1 in court to make it official.

Taylor is studying pre-law at Lipscomb University.

Taylor is studying pre-law at Lipscomb University.

Next steps: Taylor, Carrie and Jase DuRard are just starting to build a nonprofit named for John, Johnathan’s Path, that will help foster teens succeed, especially when they age out of state custody at 18.

The DuRards hope to build a series of safe, loving group homes, hope to inspire many more adults to become foster parents, hope to build a network of supportive adults to help foster kids transition into adulthood.

“These kids don’t have someone to call when they break up with a girlfriend or boyfriend, or when they get fired,” Carrie DuRard said. “I’ll raise my hand every time. That’s what Johnathan’s Path does. We’ve got you anytime.”

Reach Brad Schmitt at brad@tennessean.com or 615-259-8384 or on Twitter @bradschmitt.